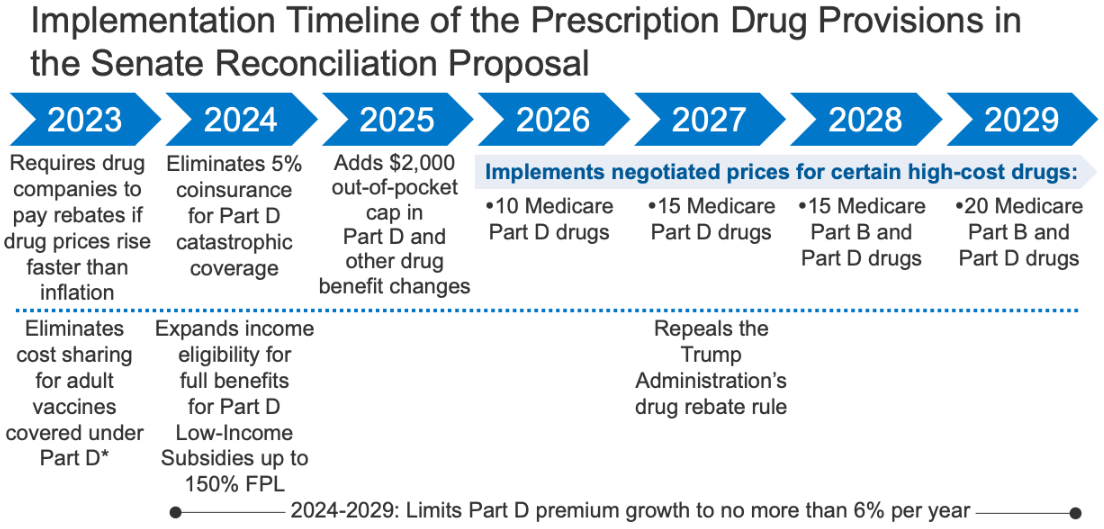

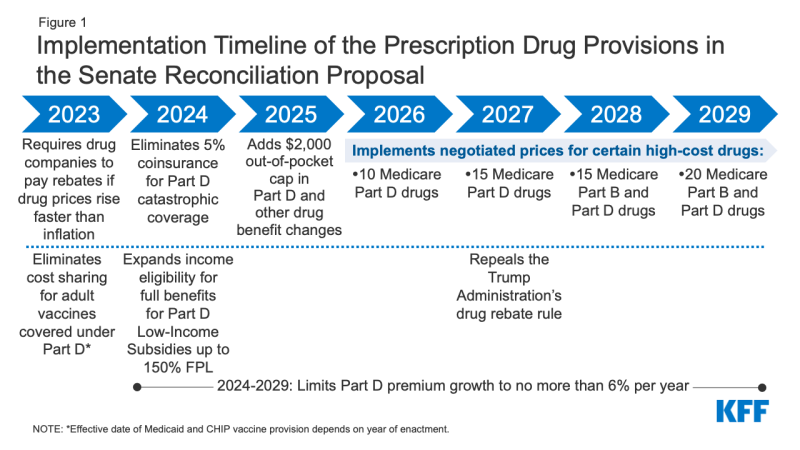

The Senate Finance Committee recently released legislative text to be included in a forthcoming reconciliation bill that includes several provisions to lower prescription drug costs for people with Medicare and private insurance and reduce drug spending by the federal government. The prescription drug provisions in the Senate reconciliation legislation would reduce the federal deficit by $288 billion over 10 years (2022-2031), according to CBO. It would also reduce out-of-pocket spending by Medicare beneficiaries and limit increases in drug prices for Medicare and private insurance. The provisions would be implemented over several years beginning in 2023 (Figure 1). This brief examines the potential impact of these provisions for Medicare beneficiaries nationally and by state, based on legislative text released on July 7, 2022.

Figure 1: Implementation Timeline of the Prescription Drug Provisions in the Senate Reconciliation Proposal

The Senate Finance Committee legislation includes two policies that are designed to have a direct impact on drug prices, both of which are similar to provisions included in legislation passed in the U.S. House of Representatives in November 2021:

- Requires the federal government to negotiate prices for some high-cost drugs covered under Medicare. Top-spending brands and biologic drugs without generic or biosimilar equivalents that are covered under Medicare Part D (retail prescription drugs) or Part B (administered by physicians) and are nine or more years (small-molecule drugs) or 13 or more years (biologicals) from FDA approval would be eligible for negotiation. The number of negotiated drugs would be limited to 10 Part D drugs in 2026, 15 Part D drugs in 2027, 15 Part B and Part D drugs in 2028, and 20 Part B and Part D drugs in 2029 and later years. CBO estimates $101.8 billion in Medicare savings from the drug negotiation provision.

- The number of Medicare beneficiaries who would see lower out-of-pocket drug costs in any given year under this provision, and the magnitude of savings, would depend on which drugs were subject to negotiation under the legislation and the price reductions achieved through the negotiation process relative to current prices.

- Imposes rebates on drug manufacturers that increase prices faster than inflation to limit annual increases in drug prices for people with Medicare and private insurance. From 2019 to 2020, half of all drugs covered by Medicare had price increases above the rate of inflation over that period (1%, prior to the recent surge in the annual inflation rate), and among those drugs with price increases above the rate of inflation, one-third had price increases of 7.5% or more, the inflation rate in early 2022. The inflation rebate provision would be implemented beginning in 2023, using 2021 as the base year for determining price changes relative to inflation. CBO estimates a net federal deficit reduction of $100.7 billion over 10 years from the inflation rebate provision due to both reductions in spending and new revenues.

- The number of Medicare beneficiaries and privately insured individuals who would see lower out-of-pocket drug costs in any given year under this provision would depend on how many and which drugs had lower price increases and the magnitude of price changes relative to baseline prices.

The Senate Finance Committee legislation also includes several provisions that would reduce out-of-pocket spending for Medicare beneficiaries:

- Eliminates the 5% coinsurance requirement above the Medicare Part D catastrophic threshold in 2024 and adds a $2,000 cap on Part D out-of-pocket spending in 2025, along with other Part D benefit design changes. In 2022, the catastrophic threshold is set at $7,050 in out-of-pocket drug costs, which includes what beneficiaries themselves pay and the value of the manufacturer discount on the price of brand-name drugs in the coverage gap (sometimes called the “donut hole”), which counts towards this amount. Under current law, beneficiaries who use only brand-name drugs in 2022 have to spend about $3,000 out of their own pockets (rising to around $3,500 in 2025) before qualifying for catastrophic coverage, and then face 5% coinsurance. CBO estimates the Part D benefit design changes would increase federal spending by $25.1 billion over 10 years.

- 1.3 million Medicare Part D enrollees without low-income subsidies had spending above the catastrophic coverage threshold in 2020 (the most recent data available), which was $6,350 that year, and would be helped by the elimination of the 5% coinsurance requirement above the catastrophic threshold. (See Table 1 for state-level estimates)

- 1.4 million Medicare Part D enrollees without low-income subsidies had annual out-of-pocket drug spending of $2,000 or more in 2020 and would be helped by the proposed $2,000 hard cap on out-of-pocket drug spending. This group includes the 1.3 million enrollees without LIS who had spending above the catastrophic threshold in 2020. (See Table 1 for state-level estimates)

- These estimates of how many beneficiaries could be helped by these changes are conservative because they do not account for expected increases in average annual out-of-pocket spending since 2020 that would increase the number of beneficiaries with spending above the catastrophic threshold or above $2,000.

- Capping out-of-pocket drug spending under Medicare Part D would be especially helpful for beneficiaries who take high-priced drugs for conditions such as cancer or multiple sclerosis. For example, in 2020, among Part D enrollees without low-income subsidies, average annual out-of-pocket spending for the cancer drug Revlimid was $6,200 (used by 33,000 beneficiaries); $5,700 for the cancer drug Imbruvica (used by 21,000 beneficiaries); and $4,100 for the MS drug Avonex (used by 2,000 beneficiaries).

- Eliminates cost sharing for adult vaccines covered under Medicare Part D, as of 2023, and improves access to adult vaccines under Medicaid and CHIP. CBO estimates these provisions would increase federal spending by $4.4 billion and $2.5 billion, respectively, over 10 years.

- 4.1 million Medicare beneficiaries received a vaccine covered under Part D in 2020, including 3.6 million who received the vaccine to prevent shingles, and would benefit from the elimination of cost sharing for Part D vaccines. (See Table 1 for state-level estimates)

- The Medicaid and CHIP provision would require vaccine coverage for all Medicaid-enrolled adults. Under current law, vaccine coverage is optional for many adults and coverage varies by state. According to a recent survey, half of states (25) did not cover all vaccines recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) in 2018–2019, and 15 of 44 states responding to the survey imposed cost sharing requirements on adult vaccines.

- Expands eligibility for full Part D Low-Income Subsidies (LIS) in 2024 to low-income beneficiaries with incomes up to 150% of poverty and modest assets and repeals the partial LIS benefit currently in place for individuals with incomes between 135% and 150% of poverty. Beneficiaries receiving partial LIS benefits typically pay some portion of the Part D premium and standard deductible, 15% coinsurance, and modest copayments for drugs above the catastrophic threshold, while those receiving full LIS benefits pay no Part D premium or deductible and only modest copayments for prescription drugs until they reach the catastrophic threshold, when they face no cost sharing. CBO estimates this provision would increase federal spending by $2.2 billion over 10 years.

- 0.4 million Medicare beneficiaries received partial LIS benefits in 2020 and could potentially be helped by the expansion of income eligibility for full LIS benefits. Annual out-of-pocket costs for these beneficiaries could fall by close to $300, on average, based on the difference between average out-of-pocket drug costs for LIS enrollees receiving full benefits versus partial benefits in 2020. (See Table 1 for state-level estimates)

- Black and Hispanic Medicare beneficiaries would disproportionately benefit from this provision because they are more likely than white beneficiaries to have incomes between 135% and 150% of poverty.

The Senate Finance reconciliation legislation also includes a provision that would repeal the Trump Administration’s drug rebate rule, currently slated to take effect in 2027. The rebate rule would eliminate the anti-kickback safe harbor protections for prescription drug rebates negotiated between drug manufacturers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) or health plan sponsors in Medicare Part D. If implemented, this rule would increase Medicare spending and premiums paid by beneficiaries. CBO estimates this provision would save $122.2 billion between 2027 and 2031.

Discussion

High and rising drug prices remain a top health care affordability concern among the general public, with large majorities of Democrats and Republicans favoring policy actions to lower drug costs. The prohibition against the federal government negotiating drug prices was a contentious provision of the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003, the law that established the Medicare Part D program, and lifting this prohibition has been a longstanding goal for many Democratic policymakers. The pharmaceutical industry has argued that allowing the government to negotiate drug prices would stifle innovation. CBO estimates that 15 out of 1,300 drugs, or 1%, would not come to market over the next 30 years as a result of the drug provisions in the reconciliation legislation.

The Senate Finance legislation would limit annual increases in drugs price for people with Medicare and private insurance, a response to public concerns about rising drug prices. While it is possible that drug manufacturers may respond to the inflation rebates by increasing launch prices, overall, this provision is expected to limit out-of-pocket drug spending growth for people with Medicare and private insurance and put downward pressure on premiums by discouraging drug companies from increasing prices faster than inflation.

The $2,000 hard cap on out-of-pocket prescription drug spending would be the first major change to the Medicare Part D benefit since 2010, when lawmakers included a provision in the Affordable Care Act to close the so-called Part D “donut hole.” A cap on out-of-pocket drug spending for Medicare Part D enrollees would provide substantial financial protection to people on Medicare with high out-of-pocket costs. This includes Medicare beneficiaries who take just one very high-priced specialty drug for medical conditions such as cancer, hepatitis C, or multiple sclerosis and beneficiaries who take a handful of relatively costly brand or specialty drugs to manage their medical conditions.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

Juliette Cubanski, Tricia Neuman, and Meredith Freed are with KFF. Anthony Damico is an independent consultant.